Saša Nabergoj

A Conversation with Moreno Miorelli and Donatella Ruttar

In 1994 you invited your artist friends to Topolove. How did this initiative emerge? When did the idea emerge and how did you develop it? What has driven you to prepare the 'festival' at the end of the road?

The village of Topolo/Topolove is defined by its boarder, loneliness, abandoned state, the difficult historic circumstances, vivid nature, language, cultural particularities, etc. We both thought that the aforementioned characteristics could encourage the creativity of artists and all those restless souls who are in a constant search of 'unusual' places, i.e. places with souls. There are places in this world for which it seems that they are waiting for a person to listen to them and they will reveal their entire wealth to her or him. Topolove is one of these places. The fact that the road ends here is merely one of the symbolic values of the village. The end is at the same time also a beginning, a person merely has to turn around and there it is. At the same time this is not a transitory place, but a final destination, which demands strong will power to set on the journey. Whoever has not yet been here and has decided to climb up to Topolove, has listened to his most adventurous and irrational thoughts. At the beginning, during the first steps of the Station, we wanted to challenge history, for history played a decisive role in Topolove and the entire Venetian hinterland. We wished to challenge the faith of the 'limited' people and check if the village of Topolove which is not marked on any map, could change into a 'station', i.e. a place of departures and arrivals with the possibility of endless encounters.

The Stazione di Topolo/Postaja Topolove (Station Topolove) is based on the hospitality of the locals, on bringing together all who participate in any way. It seems that it is becoming increasingly successful and that the crowd is on the increase. What will happen now that it has grown, how will it preserve its specifics of co-operation by all, which is usually limited with the number of people? This only functions well if there is a smaller number of people.

The audience that has visited Toplovo this year was not a crowd. This is a term that draws attention to chaos, disorder and confusion. It is often possible for merely three people to create a crowd and this was the case during the first years. Let's say that Topolove is visited by a large number of individuals who by no means create a crowd.

What criteria do you use to select the participants?

The criterion for selection is the gut feeling; a feeling of immediate connection with a person when we both feel a certain possibility for affection, respect, co-operation and solidarity. The person also has to share the same views of the world outside the frames such as the 'world of art'. There are no main co-workers, the 'Topolove' wind can blow from any side and from any circle, artistic or not.

How do the locals respond to the artistic interventions? I am especially interested in the way they respond to projects that deal with the 'glorious' history of the village, the history that some can still remember (at least from the word of mouth): for example the booklet by Valentin Gorjup or last year's project by Daniel Casali.

For many inhabitants of Topolove the Station is like a flower in the buttonhole, a sort of revenge after the decades of hard, hidden, disgraceful history (first fascism, then the cold war). They are well aware that the memory is necessary, but so is the opportunity for someone to listen to them. In this sense the locals are extremely open. During the cold war period they got used to the enforced silence and censorship, now they approached the initiatives with an open mind. They are aware that their historical experience was not in vain, that history is not 'written' merely in towns. But there are certain cases, in which the Station intensified the hate of certain individuals towards the community and themselves. But a great majority (80%) of the inhabitants is of a unified mind and heavens forbid that somebody should criticise the 'festivities' and the artists.

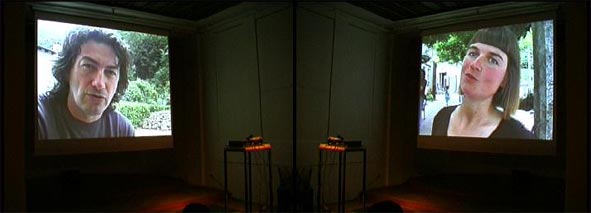

During the last ten years the projects have dealt with the village and its history. This year, for the first time, the artist is dealing with the village inhabitants, or anybody he will encounter while waiting in ambush. I am of course talking about the project by Piermario Cianio and I would like to know how this intervention was received.

This was not the first time. In the past we also had a lot of projects that demanded from the artist to 'roam' from house to house in order to collect voices, memories, emigration photographs or a simple story of personal experience. Such things were done by Merieken Verhayen, Katherine Liberovskaja, Ricardo Vivar, Gertrude Moser Wagner, Gianfilippo Pedote, Massimo Toniutti and numerous others. The inhabitants are very relaxed in front of the camera or microphone. This is because anyone can use the language that he finds closer to his line of thought, the Slovene dialect or Italian. This is followed by the curiosity to see and hear oneself again or to discover oneself and one's testimony in a work of art. All this is performed with the knowledge that they are a part of the 'game' as well as protagonists in the history, which is a bit different, a bit lighter. Let's say that they agree to be interviewed about their life much sooner than they would pose for a photograph, which would 'merely' preserve their image.

August 2004