Borut Vogelnik

The privatisation of time

It

is becoming increasingly common to hear the term global or globalisation,

even when one is talking about art, and in particularly about contemporary

art - which points to the shifts in the organisation of the art system;

in its production, distribution and consumption. The processes of democratisation

and internationalisation of art, the obvious parts of globalisation, are

at the same time its precursor, with at least one century of tradition.

In the second part of the 19th century the Independent in Paris set up

a salon with an idea that was revolutionary for its time: a show without

a jury and without awards. The extremely left-oriented artist Paul Signac

saw the potential in educating the masses, a potential which would, through

a different acceptance and evaluation of art, also change artistic production.

Artists such as Kandinsky, Klee, and Malevich wanted to articulate a visual

language that would be understandable to all, regardless of their class

or nationality. They compared the future universality of this visual language

with Esperanto, which was very popular at the beginning of the 20th century

and which was supposed to replace national languages. The key project

in the direction of globalisation and internationalisation of art took

place during the first years after the October revolution in Russia, where

the visions of many artists from all over Europe coincided with the declarations

of the communist revolution. For a short period of time the contemporary

avant-garde's production became the state art within the newly formed

Soviet Union. However, it soon became obvious that the communist leaders

did not know how to, or were not able to, take advantage of this. Of course,

Western countries tried with all their powers to prevent the internationalisation

of communism, but they accepted the concept of the internationalisation

of art. Until then the dominant concept of art linked to the nation was

first changed in the US, where the avant-garde art produced after World

War II became 'state' art, encouraged by the government and used for state

purposes (and yet in the same breath, markedly American and declared as

international or world art).

It

is becoming increasingly common to hear the term global or globalisation,

even when one is talking about art, and in particularly about contemporary

art - which points to the shifts in the organisation of the art system;

in its production, distribution and consumption. The processes of democratisation

and internationalisation of art, the obvious parts of globalisation, are

at the same time its precursor, with at least one century of tradition.

In the second part of the 19th century the Independent in Paris set up

a salon with an idea that was revolutionary for its time: a show without

a jury and without awards. The extremely left-oriented artist Paul Signac

saw the potential in educating the masses, a potential which would, through

a different acceptance and evaluation of art, also change artistic production.

Artists such as Kandinsky, Klee, and Malevich wanted to articulate a visual

language that would be understandable to all, regardless of their class

or nationality. They compared the future universality of this visual language

with Esperanto, which was very popular at the beginning of the 20th century

and which was supposed to replace national languages. The key project

in the direction of globalisation and internationalisation of art took

place during the first years after the October revolution in Russia, where

the visions of many artists from all over Europe coincided with the declarations

of the communist revolution. For a short period of time the contemporary

avant-garde's production became the state art within the newly formed

Soviet Union. However, it soon became obvious that the communist leaders

did not know how to, or were not able to, take advantage of this. Of course,

Western countries tried with all their powers to prevent the internationalisation

of communism, but they accepted the concept of the internationalisation

of art. Until then the dominant concept of art linked to the nation was

first changed in the US, where the avant-garde art produced after World

War II became 'state' art, encouraged by the government and used for state

purposes (and yet in the same breath, markedly American and declared as

international or world art).

Despite the fact that the desires of artists from the beginning of the 20th century for the establishment of an art Esperanto did not come true, belief in the global comprehensibility of the visual language and the ensuing system of evaluating art on the one hand, and acting as if global art already existed on the other hand, remain the key elements of the contemporary art system. Yet both elements within the pair (world-wide global art and the objective criteria with which we recognise and judge it) are, at the very least, problematic. There is no list of undoubtedly objective criteria for judging art, and ever since Immanuel Kant(1), we've been witnessing a whole line of theories that negate the existence of such criteria. We can also have doubts in the "globality" of global art, especially if we take into account the fact that various "isms" are, as a rule, formulated and designated only in a handful of countries. It appears that there is no global art, nor any objective criteria by which we could recognise it, yet both assumptions (global art and objective criteria) substantiate each other and, as a pair, work as an effective motivational power behind the world art system. It would be hard to accept the ubiquitously adopted criteria if there was no art that is spread throughout the world. And, on the other hand, it would be hard to claim that contemporary art is global if we did not believe in the objectivity of the criteria by which we recognise it and judge it. Even though we know that neither of the two statements is true, in a pair they open enough space for us to act as if they were true and thus co-create a system that will, in the future, confirm the correctness of these presumptions.

The principle of sovereignty granted in advance is the principle of emancipation, where the emancipated person decides with regards to his/her life, his/her battles, etc., and will only retroactively confirm the trust put into him/her. In fact it is one's own battles, one's own projects that are a sign of emancipation. When contemporary art is in question, these battles are often oriented towards the universalisation or globalisation of art. The answer to the question of under which terms the globalisation of art should be of any interest to us at all is most probably also dependant on which and of what kind of battles, if any, we are fighting.

Traditionally, the Slovene art system not only compares its creativity with the creativity of other nations, but considers itself a constituent part of a world which declares its artistic production as globally understandable and possible to evaluate objectively. The question, however, is how it co-operates in the articulation of the art system, which at some point in the future will possibly lead to the truth of a global art system. Despite comparisons of Slovene artistic production with international artistic production, there are very few comparisons between concrete Slovene works with international ones, and these comparisons are even fewer when it comes to contemporary artistic production. Despite the developed theoretical activity in Slovenia, applications of contemporary theories on concrete artistic practices are quite rare. Instead of producing a discourse on contemporary artistic practices that would establish a dialogue between international and Slovene artistic production, Slovene art criticism often behaves as if objective criteria for judging art were already articulated and as if global art were already covering the entire planet. It behaves as if somebody else had already established a global art system for us too, or as if such a system were the natural state of things. In doing so, it forgets that if there is anything obvious in this system then these are the constantly changing criteria for judging this "natural state", which it is importing all the time for this very reason. Therefore Slovenia mainly doesn't participate in forming the semantics and establishing the criteria for art - and this is logical, for how and why would one temper with the natural situation of things? It even happens that the way international art structures function are condemned from "substantialist" viewpoints for being unfair, corrupt, etc. This should not be doubted, for the art system's key presumptions (global art and objective criteria of judgement) are untrue. However, it remains unexplained by which characteristics we recognise the fairness of domestic structures.

If we return to the question of under what terms the globalisation of art should interest us we must admit that what is happening to art on a global scale is of no consequence whatsoever if everything that one is supposed to think about art is already known and if we are going to adjust to the novelties as we go along; if communication with artists and among them is reduced to the presentation of artefacts. What we have in mind here is "internal" communication, i.e. communication within the country, as well as communication with the international art world. Interest reduced to only two segments - production and presentation of artefacts - played a key role in the way dissident artists were dealt with during the Cold War. Dissident art was supposed to prove that the individual/artist is identical in the East and the West and confirm that it was only the repressive Eastern systems that prevented this identity from being affirmed also at exhibitions. Following the collapse of the communist regimes the "Westerners" started including works of art by individual "Eastern" artists into their exhibitions in order to prove the universality of artistic production. Now these artists have ceased to be proof of this identicalness, which was oppressed by communism. Instead they have become proof that there are almost no more differences between the artistic production of the East and West. (See the first letter to the public from the curators of Manifesta II). It seems that the relationship has changed completely, but the current argumentation speaks in favour of the fact that the specific narrowness of the interest has not changed. The production of contemporary art in an environment which not only does not have an adequately developed artistic infrastructure, but also is often hostile towards artistic production, is something completely different than the production of contemporary art in countries with a large gallery and museum structure which is included in international movements, and an organised market and a continuous critical-theoretical discourse on contemporary, past and future artistic production. To say that there are no more differences between the East and the West is, at the very least, unusual since we know that such differences exist in all fields, from military to economic, political, etc. As if only the artistic sphere, off all the activities in the East that are transforming in the process of transition, has changed overnight. And experts who often state that the differences have been abolished, still often make remarks that the Eastern artistic infrastructure and theory, and especially the market, do not meet western standards. As if contemporary artistic productions (or at least individual works of art from the East and the West) were comparable, but the art systems as a whole (including art distribution and consumption) were not. It seems that an individual artefact has equal opportunities to be recognised as a valuable one, regardless of its condition of production. Between the artefact and the way in which it is included into a broader system, which is differently organised within different countries, there is supposedly no relation. Why then does the West spend so much time dealing with the infrastructure, market, articulation of contemporary art production, and introduction of new technologies into art? Why, in 1948, did C. Greenberg write: "The main premises of Western art have at last migrated to the USA, along with the centre of gravity of industrial production and political power."(2) Is it not the perception of art in general which paralyses the activities of marginal spaces? The influence of the international art system is such that the marginal systems follow it, even though this dominant system behaves as if it did not exist at all or as if it existed just by coincidence, as a transitional mistake in the approach to the ideal flow from the particular to the general. Maybe we should seek the meaning of the globalisation of art within the centralisation of the reflection on art and distribution infrastructure? If this is so, then the answer to the question "Under what sort of conditions should the globalisation of art interest us?" is the following: If we are to participate in the globalisation process, then this question should be of no importance to us. And it seems that the inarticulateness of the artists and the artistic circles of the East is the point where the desires and expectations of foreign and domestic experts harmoniously complement each other.

>Ever since the beginning of the 80's, Irwin has been advocating the standpoint that the Slovene art system and the international art system are not in a relationship where establishing oneself in a smaller system would automatically lead to establishing oneself in a larger system. They are qualitatively different, and an artist's establishment in a smaller system, almost as a rule, means his/her non-inclusion in the international artistic system. Therefore one could conclude that they are not in a linear but a dialectic relation. (See Fanzin published at the Back to the USA/ Škuc exhibition, 1984). When the period of "anarchy" in the 80's, so ideal for creating a critical mass, started to transform into the so-called transitional period of the 90's, in opposition to most we did not try to melt with the Western art system, but decided to articulate our own context. That is why almost all of the projects we created in the 90's were accompanied by a publication, while the key projects (the Moscow Embassy and Transnacionala) were conceived in such a way that books were the final results. We were of the opinion that the different conditions of production in the East necessarily bring about otherness, a difference that is also inscribed in artistic production itself. We labelled this difference - and the artistic production defined by this difference - "Eastern modernism," and we decided to find out how this difference manifested itself in concrete production, being aware all the time that our activity affected the results of our inquiry. In short, we put ourselves in a position where we were the author and our own object at the same time. The first exhibition that started, as we later discovered, a ten-year project which V. Misiano later entitled "the institutionalisation of friendship" was Kapital. Alongside the exhibition we published a catalogue with the same title. Together with Eda Čufer, with whom we co-operated at all subsequent exhibitions, publications, round tables, and travels, we wrote the text "The Ear behind the Painting." This text, in which we emphasised the viewpoints we held at that time, we sent to some prominent theoreticians from the East and West, hoping that they would be moved to start a dialogue with us. The publication Kapital is therefore a collection of texts linked to the issues that were opened with the text "The Ear behind the Painting."

In 1991 we took part in the Moscow Apartment-Art International project, which addressed issues that were close to the ones we were dealing with. We prepared a one-month project called NSK Embassy Moscow(3), with which we wanted to make direct contacts with Russian artists and curators. We left for Moscow hoping that through a dialogue with people who had had experiences that were at least partially similar to ours, we would find it easier to shed light on the problems that were of interest to us. These assumptions were proved to be correct. Not only did we have a lot to tell to each other, we also became friends with some of them. We were influenced to a great extent by the Moscow artistic scene, and by the fact that we found partners in discussion. The book titled NSK Embassy Moscow, a key material product of the project, presents the lectures, conversations, and discussions which took place during the project. Apart from these texts, the book also includes some of the points which were not clarified during the project itself.

The next project took place in Munich, where Haralampi G. Oroschakoff organised a symposium and a triple exhibition in 1995. The whole project was entitled OST - Ostlicher Positionen Innerhalb Der Westlichen Welt and was accompanied by the publication of a book entitled Kraftemessen. In the same year, Ljubljana hosted two artists from the Moscow scene: Vadim Fishkin, who first came to Ljubljana as a set designer for the performances by the Noordung theatre and a while later with a solo exhibition, and Alexander Brener, who made three performances with the joint title "Street Fighter and his Limits."

In 1994 meetings of artists and curators of the now legendary Interpol

(4) project began to be organised. The core of the project was formed

by artists from Moscow and Stockholm, each of whom invited one other artist

to participate in the project. The project aimed to establish, with the

aid of several multi-day meetings, communication between the artists from

the East and West, which would eventually lead to an exhibition of artefacts

or actions that would be so closely intertwined as to appear almost like

one single work of art. The tensions between the artists from the East

and the artists from the West, which increased from meeting to meeting,

broke out into an open conflict and at the opening of the exhibition transformed

into a scandal with actual physical violence. (Alexander Brener destroyed

the central piece of the exhibition, and Oleg Kulik, who played the role

of a dog, bit a few visitors at the exhibition. He was only brought under

control by the police). It was only then that some sort of communication

truly started. Numerous texts by various authors who represented very

different viewpoints before this event started circulating on the Internet

and in other media. The conflict also reached Manifesta I in Rotterdam,

for which Interpol was a pilot project, and reached a second peak

in the late autumn of 1996, when Alexander Brener drew a green dollar

symbol on the painting White Suprematism 1922-1927 by K. Malevich,

which is hanging in the Amsterdam Stedelijk museum. At the end of this

year (1999), Irwin will publish a selection of these texts in co-operation

with the Moscow Art Magazine. The editing will be done by Eda Čufer and

Viktor Misiano.

In 1994 meetings of artists and curators of the now legendary Interpol

(4) project began to be organised. The core of the project was formed

by artists from Moscow and Stockholm, each of whom invited one other artist

to participate in the project. The project aimed to establish, with the

aid of several multi-day meetings, communication between the artists from

the East and West, which would eventually lead to an exhibition of artefacts

or actions that would be so closely intertwined as to appear almost like

one single work of art. The tensions between the artists from the East

and the artists from the West, which increased from meeting to meeting,

broke out into an open conflict and at the opening of the exhibition transformed

into a scandal with actual physical violence. (Alexander Brener destroyed

the central piece of the exhibition, and Oleg Kulik, who played the role

of a dog, bit a few visitors at the exhibition. He was only brought under

control by the police). It was only then that some sort of communication

truly started. Numerous texts by various authors who represented very

different viewpoints before this event started circulating on the Internet

and in other media. The conflict also reached Manifesta I in Rotterdam,

for which Interpol was a pilot project, and reached a second peak

in the late autumn of 1996, when Alexander Brener drew a green dollar

symbol on the painting White Suprematism 1922-1927 by K. Malevich,

which is hanging in the Amsterdam Stedelijk museum. At the end of this

year (1999), Irwin will publish a selection of these texts in co-operation

with the Moscow Art Magazine. The editing will be done by Eda Čufer and

Viktor Misiano.

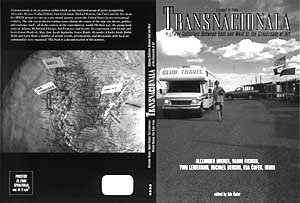

Our next project was a one-month journey from the East coast to the West coast of the USA. We entitled the project Transnacionala (5)and subtitled it "How the West Sees the East". Apart from Irwin, the following artists also participated in the project: Eda Čufer, Michael Benson, Alexander Brener, Vadim Fishkin and Yuri Leiderman. The talks among the project participants and discussion with American artists, curators, etc. which were organised in different cities were published in the book Transnacionala.

Judging by the numerous museum exhibitions dedicated to the art of the East which will take place during this and next year in Stockholm, Vienna and Paris, these issues are now being taken to a new level. It seems like this will gradually also lead to the classification of the art of the East, though not necessary in compliance with our wishes.

Notes:

(1) The present investigation of taste, as a faculty of aesthetic judgement, is not being undertaken with a view to the formation or culture of taste, which will pursue its course in the future, as in the past, without the help of such inquiries. (I. Kant, Critique of Judgement, p. )

(2) Clement Greenberg, The Decline of Cubism, The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 2, Arrogant Purpose 1945-1949, p. 215

(3) Between 10th May and 10th June 1992 the artistic action Irwin-NSK Embassy took place in a Moscow private apartment at Leninsky Prospekt 12. The action was organised by Apt-Art International and the Ridzhina Gallery. The Embassy was conceptualised as a live installation. Besides the documents and artefacts of NSK and their guests Goran Đorđević, Mladen Stilinović, and Milivoj Bijelić, the central event of the project was a one-week program of lectures and public discussions, organised in co-operation with Irwin. The lecturers were Rastko Močnik, Marina Gržinić and Matjaž Berger from Slovenia, Vesna Kesić from Croatia as well as well-known names from the Moscow conceptual, media and philosophic scene: Viktor Misiano, Valeri Podoroga, Aleksandr Yakimovich, Tatiana Didenko, and Artiom Troitsky. The aim of this event was to confront the similar social contexts of the ex-Soviet Union and ex-Yugoslavia. The encounter of individuals with similar aesthetic and ethical interests and social experience revealed that the topic arousing the most enthusiastic and intense debate was the art and culture of the 80s and the specific role it played in the transformation of Eastern Europe. (Introduction, Irwin - NSK Embassy Moscow, Irwin & Obalne Galerije Piran, 1993, p. 5)

(4) Interpol took a long time to be realised, perhaps even too long. However the temporal character, the self-becoming duration, was basically immanent to this project. The idea of this project presumed several stages. First, the curators chose artists in Moscow and in Stockholm. Then the chosen artists had to choose a partner (or partners) among their own circle or from any other place (these partners didnt necessarily have to be artists) and together create a project. The project had to possess a quality of totality, which meant that they had to develop the whole exhibition space of Färgfabriken and not only fragments. Thus, different projects, coexisting in one place, automatically should have come into conflict. That is why the next step was to be a meeting between all the participants of Interpol, and a discussion between them, resulting in a compromise. The artists had to find a way to correct their projects so that they could peacefully exist side by side. Another possibility was also taken into consideration: the first meeting could lead to the project shift towards greater interactivity, towards a situation where all the participants became involved in a collective work. That is why even an additional meeting, a general rehearsal was not excluded. (Jan Aman, Viktor Misiano, Introduction, Interpol, Stockholm, 1996, p. 5)

(5) Transnacionala is an art project within which an international group of artists (comprising of Alexander Brener, Vadim Fishkin, Yuri Leiderman, Michael Benson, Eda Čufer and the five-member IRWIN group: Dušan Mandič, Miran Mohar, Andrej Savski, Roman Uranjek and Borut Vogelnik) set out on a one-month journey across the United States in two recreational vehicles. The aim was to discuss various issues during the course of the trip: art, theory, politics, and existence itself - all in the context of contemporary world. On their way, the group made stops in Atlanta, Richmond, Chicago, San Francisco and Seattle. In co-operation with friends and hosts Goran Đorđević, Mary Jane Jacob, Katharine Gates, Randy Alexander, Charles Kraft, Robin Held, and Larry Reid, a number of artistic events, presentations, and discussions with local art communities were organised. (Eda Čufer, Introduction, Transnational, ŠOU Ljubljana, collection KODA, 1999, p. 3)

Photos:

- NSK Embassy Moscow

- Kapital

- From left to the right: Vadim Fishkin, Alexander Brener, Viktor Misiano, Ksenja Kunstoška, Gia Rigvana, Anatolij Osmolovskij, Jurij Leiderman, Haralampi Oroschakoff, Andrej Savski, Roman Uranjek, Dimitrij Gutov, Dušan Mandic, Borut Vogelnik, München 1995.

- Breakfast on the grounds of the Gates family estate in Richmond. Katharina Gates hosted Transnacionala for the three day stay in Richmond.

- Transnacionala